By Eric Hause | Copyright by the author

Legends and myths pervade the history of the coast of North Carolina, from the disappearance of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony to the mystery of Blackbeard’s buried treasure.

Most of these legends have some root in fact, and perhaps one of the most fascinating true tales involves the daughter of one of America’s founding fathers.

On a cold stormy night in 1812, Theodosia Burr Alston vanished along with the schooner Patriot somewhere off the Outer Banks. It’s a disappearance story on parr with Amelia Earhart and was all the news in early 19thCentury America. Like Earhart, her fate remains shrouded in mystery, hidden beneath the shifting sands and shoals of the Carolina barrier islands.

Theodosia was the daughter of Aaron Burr, former vice president to Thomas Jefferson, who claimed a notorious place in history as the man who killed political rival Alexander Hamilton in America’s most famous duel in 1804. However, although this is a tale of the Burr family, it begins with Hamilton.

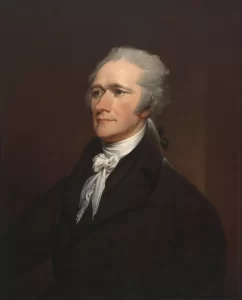

Alexander Hamilton

Hamilton was born by the sea in St. Croix and grew up with a healthy admiration for the ocean’s power. When he was 15, he wrote such a vivid description of a hurricane that ravaged his Virgin Island home that local merchants took up a collection to e send him to New York for his education.

In 1773, he cast off on his company’s ship, the Thunderbolt. Somewhere off Hatteras, young Hamilton’s ship was caught in a terrific gale. As the captain hove to in an effort to ride the storm out off the Cape, the galley caught fire, and for 12 terrifying hours, the crew and Hamilton fought the blaze. Once under control, the heavily damaged ship limped northward to Boston.

Legend has it that Hamilton would never forget that terrifying night off Cape Hatteras. He swore an oath that should he ever be in a position to do so, he would erect a lighthouse on the treacherous Cape as a warning to all other mariners.

Hamilton went on to become one the leaders of the Revolution and eventually a member of President George Washington’s cabinet. As Secretary to the Treasury, he lobbied for funding of a series of lighthouses along the east coast. The first one was constructed in 1791 at Cape Henry, Virginia, 200 miles north of Cape Hatteras. It wasn’t until 1795 that got around to funding the first lighthouse at Cape Hatteras. Nine years later, it was completed, and although it has long since succumbed to the sea, ‘‘Mr. Hamilton’s Light’‘ as it was called served its purpose well.

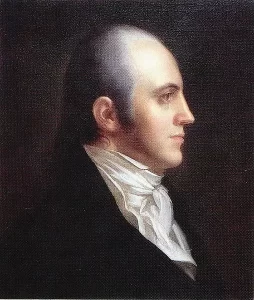

Aaron Burr

It was during this time that the new Republic was going through arduous growing pains, and during his rise to political power, Hamilton befriended a young New York lawyer named Aaron Burr. They had initially met while serving under Washington during the Revolution. After the war, Hamilton found Burr’s political ambitions matched his own, and together they worked together forge a new nation.

Burr had married in 1781 and two years later his wife gave birth to their only child, a daughter they named Theodosia.

From the start, father and daughter were connected in ways very few are. Theo’s love for and devotion to her father were rivaled only by Burr’s nearly obsessive parenting. Burr spent many of Theo’s formative years in Washington, and when she was 10, they began a 20-year legacy of correspondence that remains to this day as a record of their strong relationship. So prolific was their correspondence that it was catalogued in a best-selling book entitled Dear Theodosia.

When Theo’s mother died of cancer in 1794, she easily stepped into the role of mistress of Richmond Hill, the family home in Albany. She supported her father’s rising political career by hosting grand parties at the estate. Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton were regular visitors, and Theo was charming and gracious to them all, all the while remaining close by her father’s side.

When Theo’s mother died of cancer in 1794, she easily stepped into the role of mistress of Richmond Hill, the family home in Albany. She supported her father’s rising political career by hosting grand parties at the estate. Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton were regular visitors, and Theo was charming and gracious to them all, all the while remaining close by her father’s side.

Theo had many suitors, but she did not meet her husband until a dashing young southern aristocrat by the name of Joseph Alston visited Albany in 1800. Theo soon after confided to her father that she was falling in love with Alston, and in February 1801 they were married.

Theo left Richmond Hill to make her new home in South Carolina, where she would spend her days supervising two plantations and the Alston family home. She loved her husband, but often missed her New York home, particularly her father. She wrote to him that the hot, humid climate and swampy Lowcountry was no match for the beauty of Hudson River Valley.

In May 1802, after a very difficult labor, Theo gave birth to a son named Aaron Burr Alston. She never completely recovered from the birth. When her husband was elected Governor of South Carolina, her weakness coupled with her new demands as First Lady of South Carolina began to take their toll. She made several visits to health resorts with no lasting effect. But her dedication to her family never wavered.

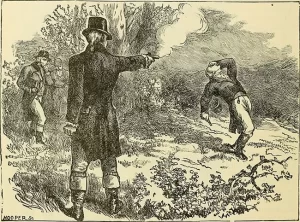

Contemporary artist’s rendering of the famous duel.

In 1804, Aaron Burr’s political career disintegrated. The heated political climate of the day had found Burr and Hamilton on opposite ends of the political spectrum. Their rivalry descended into a war of personal insults waged in the northern newspapers until Burr, outraged beyond apology, challenged Hamilton to the duel that would kill the former vice-president.

Although Burr was charged with murder, Theo stood by her father. She traveled to New York several times during the long trial and was elated when he was finally acquitted. But Burr became a bitter man. He longed for political power and allegedly planned his revenge with a scheme to convince several western states to secede and place him at the head of a new government.

In 1807, he was again arrested for conspiracy. And again, Theo decried his innocence.

‘‘The knowledge of my father’s innocence, my ineffable contempt for his enemies, and the elevation of his mind have kept me above any sensations bordering on depression,’‘ she wrote to her husband from New York.

After an arduous year-long trial, Burr was once again acquitted, and he left the country, a once-powerful patriot in voluntary exile. Theo returned to South Carolina, the ordeal adding to her increasingly frail health. The final blow came in June 1812, when her son died of tropical fever.

Theo, Burr, and Alston were all inconsolable over the loss. ‘‘You talk of consolation,’‘ she wrote to her father. ‘‘Ah! You know not what you have lost. I think omnipotence could give me no equivalent for my boy.’‘

Burr returned to New York, and in December 1812, he convinced Theo to come home for the holidays. It would be their first visit in five years. Alston, however, was reluctant to allow Theo to make the ocean voyage north. The country was at war with Britain again, Theo’s health was still fragile, and there were rumors of pirates along the North Carolina Outer Banks.

Theo’s insistence won, and Alston wrote a letter to the British Navy, which was blockading the coast, requesting safe passage for his wife. Aaron sent a trusted physician and friend, Timothy Green, to accompany his daughter, and on December 30, Theo, Dr. Green, and a maid boarded the schooner Patriot in Georgetown.

The American government had hired The Patriot to harass British shipping, and her hold was filled with loot from these raids. In order to disguise the ship’s true identity, the captain stowed the guns below and painted over the ship’s name on the bow. They lifted anchor late in the afternoon and set sail for the open sea. It was the last time Alston would ever see his wife.

The journey to New York normally took five or six days. After two weeks had passed with no sign of the Patriot, Burr and Alston became frantic. Alston wrote, ‘‘Another mail and still no letter! I hear too rumors of a gale off Cape Hatteras at the beginning of the month. The state of my mind is dreadful!’‘

In New York, Burr had already reached the inevitable conclusion. When a friend offered hope that Theo was still alive, Burr replied, ‘‘No, no, she is indeed dead. Were she still alive, all the prisons in the world could not keep her from her father.’‘

A schooner similar in style to the Patriot.

The Patriot had disappeared without a trace. Later it was learned that the British fleet had stopped her off Hatteras on January 2. Governor Alston’s letter worked, and the schooner was allowed to pass. Later that night, a gale arose and scattered the fleet.

Beyond that clue, no more was known. Burr sent searchers to Nassau and Bermuda with no success. Why he neglected to send them to the Outer Banks remains a mystery for it is there that Theo met her fate.

The evidence is compelling and first surfaced in 1833. That year, an Alabama newspaper reported that a local resident and confessed pirate admitted to participating in the plunder of the Patriot at Nags Head and the murder of all on board.

Fifteen years later, another former pirate, ‘‘Old Frank’‘ Burdick, confessed a similar story on his deathbed. He told a horrifying story of holding the plank for Mrs. Alston, who walked calmly over the side, dressed completely in white.

He said she begged for word of her fate to be sent to her father and husband. He went on to say that once the crew and passengers had been murdered, they plundered the ship and abandoned her under full sail. He also mentioned seeing a small portrait of Theodosia in the main cabin.

Perhaps the most intriguing evidence to support this theory revolves around that painting. In 1869, a Dr. Poole from Elizabeth City was called to the bedside of an ailing old Banker woman in Nags Head. The woman was related by marriage to families who had once made their living by plundering vessels wrecked along the beaches.

The doctor noticed a stunning portrait of a young woman dressed in white hanging on the wall of the woman’s shack. When he commented on the beauty of the subject, the old woman offered an astonishing explanation.

She told Dr. Poole that one night ‘‘during the English war’‘ a pilot boat had drifted ashore at Nags Head at the height of a winter’s gale. The boat was abandoned with all sails set, and the name on the bow had been painted over. In the main cabin, the Bankers had found several trunks and women’s belonging’s scattered everywhere. They also found the portrait, which one of the looters took as a gift for the old woman.

The ailing woman had no money with which to pay Dr. Poole, so she offered him the 12-by-18 painting instead. The portrait generated much publicity when Dr. Poole returned to Elizabeth City, and several years later, a descendant of the Burrs came to see it. She immediately identified it as Theo because of the subject’s resemblance to other members of the Burr family.

There is no record today of what Theo carried aboard the Patriot that fateful day. It certainly would be in keeping with the devotion she felt to her father to have such a fine portrait in her possession as a gift to him. Yet through such inconsequential details are myths made, and for now, the truth lies buried beneath the shifting sands of Nags Head.

The irony, however, is inescapable. Somewhere along this shore, where her father’s nemesis had erected a lighthouse to save her, Theodosia Burr Alston lost her life on a stormy January night. And although we may never know exactly how that happened, a suicidal poet may have touched on why.

In 1894, a very young Robert Frost came to Kitty Hawk. Suffering from acute depression, he felt the need to get away from the pressures of life, and as many similar people do, he came to the Outer Banks.

One night, he crossed over the Kitty Hawk beach and walked with a member of the local lifesaving crew on patrol. The patrolman told him Theo’s story, and it moved him deeply. Years later, he would recount the experience and her tale in one of his lesser-known but moving poem, Kitty Hawk:

‘‘Did I recollect

how the wreckers wrecked

Theodosia Burr off this very shore?

’Twas to punish her

but her father more.’‘