Jackson Square was deserted on this oppressive Labor Day Monday night inhabited only by the fortune tellers and tarot card readers who floated like spirits between candlelit tables.

I was there because I had chased a guy to New Orleans for Southern Decadence. He and I had struck up an online relationship that I guess we both hoped would grow stronger when we met in person. Alas, the spark wasn’t there, so he spent the weekend at a blackjack table in Harrah’s while I discovered the pleasures of the Big Easy’s annual gayfest

As the latest number in Eric’s Big Gay Failed Relationship Tour, he had flown back to Texas earlier that day without a goodbye. All the other revelers had headed home as well, and tonight I had the city all to myself.

I climbed the steps of Saint Louis Cathedral and sat on the cool marble porch in the darkness. Thunder rumbled ominously in the distance.

I thought about the sequence of events over the past year that had led me to this moment, beginning with my tenure as marketing manager at an internet startup in Norfolk. The company, Great Bridge, was one of Landmark Communications “new ventures.” I had already worked in two previous new ventures that had failed miserably after only a few months, and I should have known better this third go round because now it was certain that Great Bridge was going to meet the same fate.

I had been in San Francisco in the days prior to my New Orleans junket to help convince Sun Microsystems to buy out the company. All I remember about those few days was standing in the middle of the bar at the top of the Marriott Marquis in downtown San Fran, some douchebag marketing person from Sun in my face talking about “the big idea.” I was so sick of that jargon and those inane conversations, and I tuned him out, walked over to the bar’s magnificent floor to ceiling windows, and watched an amazing sun burn out as it sank into the Pacific.

My career had wobbled wildly since moving to Norfolk in 1997. Now it looked as if I was about to be unemployed for the first time since I started working at 14.

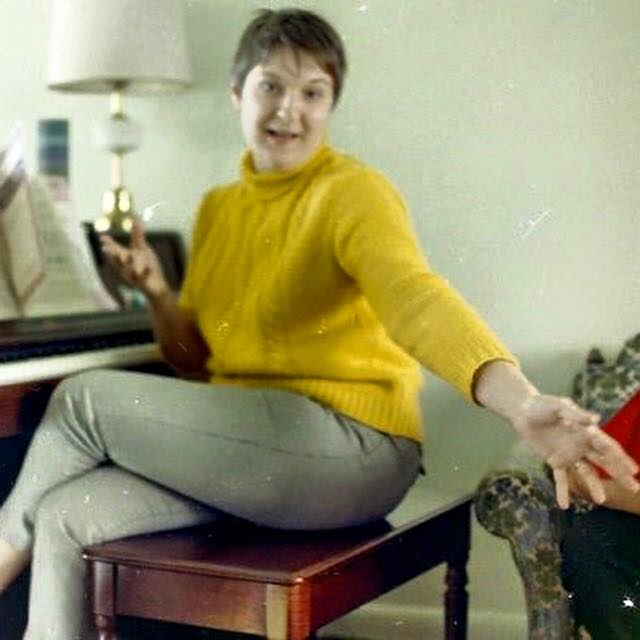

On top of that, my best friend since high school, was battling ovarian cancer in Atlanta, and she was losing. Two months earlier, I traveled to see her for what would be the last time. She was emaciated, and her eyes were sad. Her husband took her daughter—my goddaughter—out for a few hours so she and I could spend some time alone.

We sat on a swing in the backyard, and I held her hand. We had been through so much together since we were teenagers: growing up in dysfunctional families, the pain and joy of high school, a failed marriage, a new marriage, and finally, giving birth to and raising a wonderful little girl. Now, at 40, she was dying.

We sat in comfortable silence for a while. She was the only person in my life with whom silences didn’t feel awkward. Finally, I asked, “What do you want me to do?”

Laurie looked right into my eyes and said, “Make sure my family is ok.” I know then this was the last time I would ever see her.

•

As I sat on the steps of the cathedral with the storm grew closer. I recalled that promise to my dying friend, and I shed a few tears. Just as I was contemplating heading back to the hotel, the low soulful baritone of a man singing an old hymn flowed out from the darkness beneath the porch archways behind me.

“Mama put my guns in the ground

I can’t shoot them anymore

That cold black cloud is comin’ down

Feels like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door.”

I listened for a moment, entranced. Then as if God himself was coming down a deafening clap of thunder rattled the Square. I hurriedly headed back to the hotel, the message loud and clear: big changes were coming.

•

Back in Norfolk the next day, at a companywide meeting, the president made it official: Great Bridge was closing on Friday, September 4. All employees would receive a severance based on their salary level, and I was happy with mine. What made me happier, though, was to be out of the internet business. It had been a terribly nasty and stressful journey full of greedy, boastful people for whom I didn’t really care.

That last day was a gorgeous late summer offering: sunny and cool with cloudless bright blue skies. I collected my check before lunch, literally skipped to the parking lot, and drove home to my condo by the Bay. Tom Petty’s Free Falling came on the radio, and I sang it louder and more joyfully than Jerry McGuire. My plan was to do nothing but sleep, sit on the beach, and deal with the PTSD that had characterized the past two years.

I was going to let the next “big idea” find me.

•

The following Tuesday morning, my cell rang at 9:30. It was my brother. He never called this early, and I knew something was up.

“Turn on the TV!” he yelled. “A plane just hit the World Trade Center!”

The rest of that day was a slow-motion nightmare. Like everyone, I watched the horror in Manhattan unfold. At one point, I contemplated packing a bag and evacuating. The fact that I lived right next door to the world’s largest Navy base did not escape me. I somehow got a grip and opted for a calming walk on the beach.

The day was another stellar one, except there was no one in sight. I mean, no one. The Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel and the port had been closed, and the normally busy traffic coming in and out of the harbor had ceased. All air traffic had been grounded. The only sound was the gentle breeze, broken by the road of three F-16s leaving Langley, headed for DC.

I could have been the last person on earth.

The next few days were a blur. I watched from the beach as the USS Enterprise departed for the Middle East, draped in American flag bunting mimicked by the throngs of flag-waving people watching from shore. I talked to Laurie later that week, and I could tell she was failing. I stayed up almost all night every night and slept late into the next day. I drank way too much.

I also passed many of those days writing things like this in my journal:

9/16/2001, Norfolk

“I know I will survive all that’s happened lately. I know it will ultimately make me a better person. But tonight, grief has me in its grip and is shaking me to the core. Death is all around, and that long black cloud is coming down.” The world had changed, and I was beginning to understand that I had changed with it.

Four days later, I got the call I had been dreading. It was Matt. “Eric, she’s gone,” he said.

“I knew that’s why you were calling,” I said, my breath catching in my throat. “Was she at peace?”

“She was, and she had no pain,” he said. “And you’ll appreciate this: her last words were, ‘I can’t fight this anymore, and I want to go home’.”

I smiled at the thought. She and I had always shared a similar spirituality, and we both knew that we have been on this planet many times before and would be here again. I also knew that she’d be waiting for me when I went it was my turn to head home.

I told Matt that I would rent a car in the morning and drive down. I damn sure wasn’t going to fly.

•

“Would you like to speak at the service?”

It’s Joan, Laurie’s mom, asking me six hours before the service. She is a small, diminutive woman, from all outward appearances meek and unassuming. And yet, she is the one who stood by her daughter’s side for over a year. I cannot imagine what that must have been like for her to watch her oldest child die.

I have always had mad respect for Joan. Back in the Seventies she took both her daughters out of an abusive marriage and started all over again. That was no easy feat in those days, especially for a woman who had no formal education or work experience.

She had practically raised me as a teenager. I spent more time at her small duplex than I did at my own house, and that tiny dwelling became my refuge. Laurie and I gathered there with our friends on Friday nights to watch “Dallas” or play cards. We skipped school and sat on her bed, smoking Merits and listening to Foreigner or Styx records.

Joan knew but didn’t really care. She had seen worse.

When I was with Joan, I was always reminded that many families aren’t comprised out of your immediate one. Over the years, I had taken to calling her mom. She was a sight better than my own mother, who at that time was battling alcoholism.

I thought about speaking at the service. I knew that it would be tough for Matt to get up and speak. And I knew Joan was asking me because she was aware of that.

I had stood up at every pivotal event in Laurie’s life. I was in her first wedding in 1983, although I knew then that she was making a mistake. Five years later, I drove home from Greensboro in the middle of the night after she called me in hysterics to tell me that she had uncovered her husband’s infidelity. I found her curled in the bathroom floor, crying unmercifully.

I was at her pinning ceremony when she became a nurse. When she married Matt, I was there, lighting candles and toasting. I was in the hospital waiting room in Raleigh the night my goddaughter Sarah was born, and I was on the altar at her Christening, proudly accepting the role as her godfather. I remember her joking with me that if she went before I did, I would have to grow up and be a father figure.

I told Joan that I would speak, that I had no idea what I would say, but it would be an honor.

Matt, Joan, Sarah, Laurie’s sister Barbara and I piled into Joan’s Park Avenue. On the seat between Joan and me was the wooden box containing Laurie’s ashes. The sky was gray and drizzling.

We stopped by Barnes & Nobles to buy Sarah a “Bob the Builder” book, a mundane chore on this exceptional day. While we were there I discovered what I was going to say. I bought a single red rose and the small paperback which would serve as the foundation of my eulogy.

We passed a cemetery on the way to the funeral home. I turned to see gaggle of geese fly low over the mute, gray headstones. Matt steered the car into the lot of Lutz Funeral Home, put it in park, and we sat silent for a moment, all of us close to tears.

“OK, we can do this,” he said. Joan was crying softly. Somehow, we got out and went inside, Matt bearing the box. The moment had come to say goodbye.

•

Here’s what I remember from the service:

Before it began, I walked past the funeral director’s office and overheard Matt talking to him about the untested vocalist who was to perform “Ave Maria”. It was Laurie’s favorite song, and Matt was concerned. The last time they had hired a vocalist on someone else’s recommendation had been at their wedding seven years earlier. She had mutilated “Ave Maria”.

“It’s not that I don’t trust your judgment,” I heard him say. “I just don’t want my wife coming back to get me because this girl screwed up the song.”

I walked into the empty chapel with Sarah by the hand. We were alone. It had taken her a few hours to get used to me last night, but now she didn’t leave my side. We walked up to the altar where a family portrait of the three of them stood next to the box of ashes amid a sea of flowers. I laid the single red rose next to the box while Sarah wandered up on the stage. The tears came, and then Sarah tugged my hand.

“I know where mommy is,” she said.

“Where is that?” I asked.

“Right here,” she said, pointing to the chair next to her. “And up there,” she said, pointing up.

I smiled and wished we could all remember what it was like to be a child, in touch with the forces on the other side, in tune with the fundamentals. As we get older, life dulls the signal.

People, some familiar, most not, began flooding into the Chapel. I never have been at entirely at ease in situations like this, regardless of the occasion: weddings, graduations, and funerals. I always wanted to laugh or fidget nervously. But today, I felt this heat radiating from somewhere within, and it calmed me.

The holy man, the same man who married Matt and Laurie, got up to speak, and before I knew it he was calling my name. I pulled my heavy body out of the pew and walked to the altar. When I looked up into the faces of the mourning congregation I knew the time had come for the final testament.

I told those people how Laurie was the best friend I have ever had. Ever will have. I told them how she was the first and only person up to that point who accepted me as I was from day one and loved me unconditionally for it. I told them that she was not only that way with her friends, but with her husband, her daughter, her sister, and her mother.

Then I pulled out the small paperback with the blue feather on the cover. “Illusions” by Richard Bach. I read the very same passages that she and I adopted as our mantras so many years ago, back in the woods of eastern North Carolina.

“The mark of your ignorance is your belief in tragedy. What the caterpillar calls a tragedy, the master calls a butterfly.”

“Do not be dismayed at goodbyes. For a goodbye is necessary before you can meet again. And meeting again is certain for those who are friends.”

And finally: “Your true family is measured not by bonds of blood but of respect and joy in each other’s lives. Rarely do members of the same family grow up under the same roof.”

I returned to my place in the pew and the sorrow came, horrible, overwhelming, inundating. Sure enough, she was gone. An unknown hand passed me a Kleenex from behind. As comforting as those words from Richard Bach were 25 years ago, today was an utter loss. And it hurt so badly.

It was the first of a long, continuously unraveling realization that Laurie was dead. That so many people were dead. And that I was going to die, too.

•

Back at Laurie and Matt’s house, I wandered through the sea of unfamiliar faces, working the PR persona that I had become so adept at wearing in stressful situations. The acute sadness that poured out of me at the service had dulled into a gentle heartache and I found more comfort among the people that also loved and missed Laurie.

Matt is in the kitchen with Sarah and his parents gathered around the table. Joan and Barbara are sitting in the living room with their Aunt Bett, a 75-year-old nun. Laurie’s estranged father sits silent and alone in the den watching television. That’s pretty much the same thing he had done for the past 40 years.

It felt as if we were at one of the many parties we threw over the years, and these are all our friends, come to have a good time, to drink, to laugh, to share stories.

Laurie is upstairs, late as always, in the “Lab” as we used to call it putting on makeup, curling her hair, and getting beautiful. Typical Leo. It was about now that I would go up there and burst into the bathroom.

“What in the hell are you doing up here, incubating?” I’d say, feigning impatience.

Without looking away from the mirror, she’d glance up at me and raise her eyebrows. “Perfection cannot be rushed,” she’d warn. “Go away.”

I’d laugh, knowing it was all part of our shtick. Then I’d go back to the party, killing time, anticipating her entrance, which was usually a gentle drift down the stairs, nonchalant and casual, somewhat removed.

Instead, I find myself sitting next to her Aunt Bett. This is one grand old dame. A bit overweight, possibly a lesbian, very Midwestern. This woman had traveled all over the world in her life, learning four languages and visiting places most of us would never even read about.

I sit in the uncomfortable dining room chair next to her. She gently places her hand on my arm and gives me a mysterious Mona Lisaesque smile.

“You’re quite the poet,” she says. “Your words at the service today revealed that.”

I thank her for the compliment.

“You know, Laurie talked about you often. She told me a few years ago that you were her best friend.”

The tears were suddenly close and threatening. Somehow I managed to shelve them for the moment. “She was my best friend, too,” I gurgled.

“But I bet a lot of people don’t really know what that means to you,” she said. I gave her a small nod. No, they really didn’t.

She leaned in close. “I think I know what it means,” she whispered. “I think it means that you are a very independent, reserved loner, despite your gregarious nature. And she was the only person who truly understood the real you.” I looked directly into her eyes. “And I bet you don’t think you’ll never meet another person who knows you like she knew you.”

I felt my shoulders slump. She had pegged me, and that was too close for comfort.

“You’re a very insightful person,” I said with a feeble smile.

She sensed that I was tottering on the edge of despair and gripped my arm for a brief second, smiled, then turned her attention elsewhere.

Just as a woman of God should do.

•

From my journal, September 26, 2001, Atlanta:

Tonight, I’m sitting at a desk surrounded by her pictures: her and Matt at their wedding, her and infant Sarah, her with Joan and Barabara. And of course, she and I at the peak of Mount Mitchell smiling broadly. We all loved the North Carolina mountains and spent many a long weekend as an extended family in Ashville or Blowing Rock.

Across the hall, Matt sleeps in their bed, alone. Everyone else is asleep as well. We’ve stayed up late the past few nights, reminiscing, laughing, crying, grieving, remembering.

Earlier tonight, Matt suddenly said, “You know what, we’re all here now. Why don’t we drive up to Asheville and scatter her ashes this weekend?”

It was decided, and the next morning we made the journey up to Laurie’s favorite spot, Craggy Gardens on the Blue Ridge Parkway to cast her ashes into the wind. Meanwhile, 900 miles away, New York City continues to sift through ashes of another kind.

We all must become intimately acquainted with grief. What we do with that is contingent upon our ability to allow it to lift us up or cause us to succumb to the darkness.

•

From my journal, November 27, 2001, Norfolk:

Two months since Laurie’s death, the attacks on New York and DC, and the failure of Great Bridge. I feel like I had dived into a deep, cold, black lake and I am just now regaining the surface.

I am changed. I don’t understand the complete picture yet, but I know the events of September have fundamentally altered my perception of life on this planet for the better. And just in time. I was no doubt headed for a breakdown of some kind.

As sad as I am over losing my best friend, as distraught as I am over the sorry state of humanity, and as anxious as I am about being unemployed, there is this bright, calm center in my heart and mind where none existed before. Gratitude for all that I do have? Gratitude for the experiences of the last two months?

A couple of nights ago, I had a dream that I was alone walking along a beautiful forest path, It was autumn, and a gentle breeze sent vibrant leaves tumbling to the ground around me. I came to very narrow and rock-strewn creek crossed by a narrow footbridge. As I looked up to the at the other side, Laurie was already standing there grinning at me. In my dream, I grinned right back, and in my dream, I heard her voice say, “We were right. And it’s beautiful.” With that, she gave me a final grin, turned, and vanished into the forest

There’s so much of the story yet to be written, but right now, I don’t have anything else to say.

For now, I’m floating, waiting the next big idea to come.

•

Epilogue, posted to Facebook, September 21, 2021

File this under “A Universe That Works in Mysterious Ways.”

Remember my blog post last week about my experience of September 2001? So yesterday I saw a post on my goddaughter Sarah’s IG page that she was on the OBX.

Keep in mind I haven’t seen her or any of Laurie’s family in 20 years. So I messaged her, she replied, and today, almost 20 years to the day that Laurie died, I drove down to meet what I thought was just going to be Sarah and her boyfriend in Manteo only to find not only my goddaughter, but Laurie’s sister, Barbara, and her mother, Joan.

It was cloudy down there most of the day, and as I headed home west across the Wright Memorial Bridge at sunset, the clouds broke open. The most glorious beam of sunshine illuminated the road in front of me and cast orange diamonds on the Sound.

I’m just getting home and my heart is full from a wonderful day of laughing, remembering Laurie, and reliving tons of fantastic memories with people who’ve been in my life since I was 16.

Thanks, Laurie, for arranging it all.