My mother saved my life. And she had to almost die herself before she was able to save mine.

In 1987, she finally stopped drinking after nearly succumbing to 35 years of alcoholism. And it was shortly afterwards that she asked me during a quick weekend visit home if I was gay.

I was in the closet up to that point. I moved away from my small eastern NC hometown three years before and was in the middle of my first real love affair in the big city of Greensboro.

When I arrived at my parent’s home that Friday afternoon, I called my boyfriend to let him know I had made it. My mother was in the adjacent bathroom, putting on makeup before going to her evening Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and listening in on our conversation.

When I hung up and walked past the bathroom, she stopped me.

“I want to ask you a question,” she said, not looking away from the mirror as she continued her makeup application. “And if you don’t want to answer, you don’t have to.”

“OK,” I responded.

“Exactly what is the nature of your relationship with Danny?” she asked.

In that moment, my thoughts went down three drastically different paths:

- I can continue my miserable existence as a liar.

- I can say “None of your business” and walk away.

- I can tell the truth because if she’s asking, she already knows.

I picked door #3.

“I see,” she said, still not looking away from the mirror. “Well, let me finish putting on my makeup, and we’ll talk before I go to my meeting.”

By the time she finally blew into the living room where I had been sitting for 15 minutes chewing my fingernails, I was a wreck.

She sat down with a big sigh and said, “First of all, I’ve known you are gay for some time. Don’t ask me how because I don’t want to embarrass you.”

I silently went through all the Sears catalog male underwear pictures I had stashed under my bed and my unhealthy obsession with all things Stevie Nicks, but I gave away nothing. It didn’t matter. Mothers always just know.

“More importantly, I’m glad this is out because I know what it means to keep a horrible secret and how it can kill you, and I don’t want that for you.”

Immediately the gigantic oppressive steel block that had been resident on my heart for years was lifted. I knew she knew, and she was cool with it.

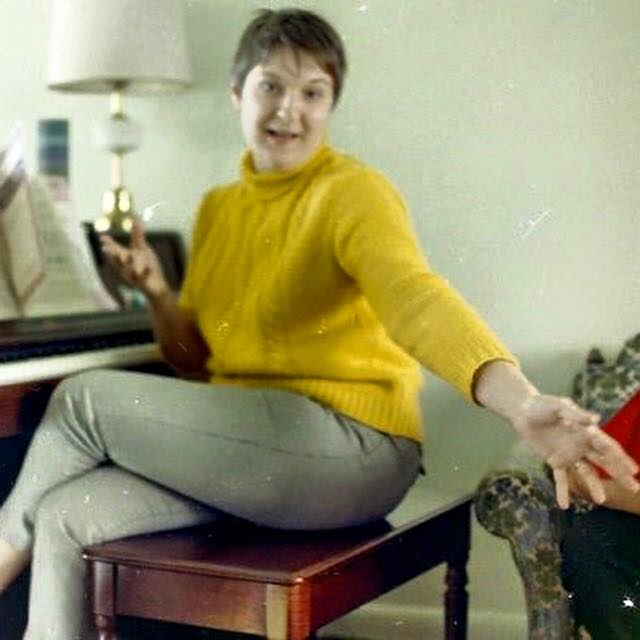

For the next 20 minutes, she talked to me about being in college at the University of Michigan and hanging out with the gay guys: playing piano at their parties, having them serve her drinks and light her cigarettes. “ I was, as you might say, a fag hag.”

I loved her so much in that moment.

She then went on to tell me that my future father, a Southern Baptist from the mountains of North Carolina whom she was dating in college, tried to forbid her to hang out with the queens.

“And I put a stop to that right there,” she said. “If he couldn’t accept my friends, I couldn’t accept him.”

How in the world those two diametric opposites ever made it work is beyond me, but they were in love for 50 years. More on that later.

“Speaking of your father, are you going to tell him?” she asked.

I was still flabbergasted by this little ambush, and I had not moved that far ahead in my thinking. “Um, probably not this trip,” I said. “But I will.”

I quickly added, “And don’t you tell him, either.” My mother was huge drama queen, and she excelled in the role of gossip bearer.

She nodded in silent agreement. But it wasn’t an enthusiastic nod, and I already knew she wouldn’t be able to stand it for very long.

She wrapped up our little chat by saying, “My only hope is that you’re careful with your health.”

I smiled. “I’m aware, mom, and I’m ok.”

With that, she gave me a kiss and a hug then walked out the door to go save some more lives at her AA meeting. She went to those meetings religiously three times a day for the next 35 years until she physically couldn’t any longer.

Two nights later, I had just arrived back in Greensboro, and she called.

“Well, I had to tell your father,” she bleakly intoned as if she’d been tortured. I wasn’t buying it.

“Really? You HAD to tell him?”

She went on to explain how, at the dinner table earlier that evening, my father inquired if I had made it home safely. According to her, one thing led to another, and, well, it just came out.

After a quick flash of anger (because she was ALWAYS doing this shit), I felt a second huge stone lift, and it was OK. I knew she planned it that way all along. Truth was, it wasn’t fair to ask her to keep that secret.

“What was his reaction?” I asked.

“Well, the first thing he said was, ‘He doesn’t have to be that way’,” she replied. “And I said, Robert, you just don’t get it, do you?”

I got it. He was a product of the stereotypical rural Southern Baptist upbringing, complete with Jesus and Confederate flags and suffering. But I knew that he was doing his best to be a different progressive person, and my Chicago liberal mother was his guide on that journey.

My father and I never overtly talked about my homosexuality. But from that moment on, our relationship changed for the better. He began hugging me when I arrived home and when I left. That was a first.

Over subsequent years, he met many of my gay friends, accepted us all in his house and invited us to sail on his boat. He met most of my love interests, too, and treated them all with gentility and respect.

And, thank God, just as he was beginning to slide downhill into the abyss of Parkinson’s, he met Andrew, my future husband, and embraced him completely.

Don’t get me wrong. It was never easy with my mother or my father or my brothers—we are all passionate, volatile artists prone to drug and alcohol abuse, violent outbursts, and loud, outrageous behavior. In fact, we’re ALL drama queens.

But in the end, when both of my parents were ill and in dire need of rescue, I took care of them.

Shortly after my father died, my mother was next. When she succumbed to dementia, I brought her to Norfolk and placed her in a nursing home not far from my home. At that point, she was incoherent, and there wasn’t much left.

Two months before she died, I rode with her in an ambulance to the doctor’s office. We were in the waiting room, and she was strapped into a stretcher, agitated and out of her mind. I pulled up some old family photos on my phone, hoping it would calm her down.

I scrolled through them with one hand while holding hers with my other and talking to her quietly.

“Here’s dad, remember this picture? And there’s Jon and Evan, and your granddaughters…”

She began to relax until finally we were laughing. In that moment, she looked me in the eye and said clearly, “I don’t know what I would do without you.”

I couldn’t respond because the tears were so close. But I wanted to say the same thing to her. I probably would be dead if not for her unconditional love on that summer day in 1987.

Those were the last coherent words she said to me, and shortly afterwards, I held her hand again as she slipped away.