My high school friend Henry Wooten has been on my mind today.

Our parents were friends–everyone knows everyone in our small eastern NC town–but we didn’t meet until 10th grade when we both came to the same high school and joined the stage band.

He was the first piano player, and I was the second. He was much better than I was, and at first I felt a bit intimidated by him.

Then one October day, after a poem I had written appeared in the school’s literary magazine, he approached me.

I didn’t think the poem was anything earth shattering. It was an analogy between money and consumerism, and an evil bird made of gold that swooped down to consume the people who were blinded by their greed.

In other words, an adolescent attempt at a well-worn literary device.

But Henry complimented me. He said it struck him deeply, and from that moment on, we were equals.

As we began spending more time together, we bonded through our commonalities: love of music, poetry, spirituality, and pot. Combine all of those things, and you get some meaningful conversations.

Of course, it was the 70s, so I don’t remember all of them, but the connection was still there.

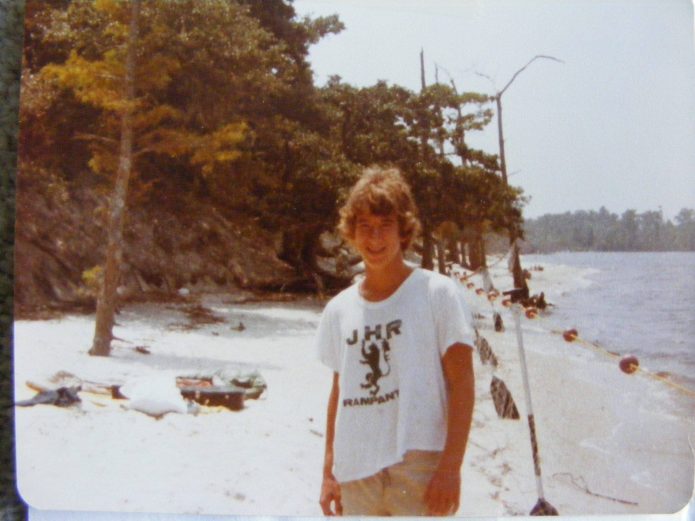

Two summers later, we worked as co-counselors at a summer camp, which was where we really bonded. It all came together one of the last nights of that summer, when the entire camp had gathered in the lodge for movie night.

Unfortunately, the projector wasn’t having it. To kill time, Henry picked up his guitar and began strumming “Stairway To Heaven.” Without a word or invitation, I sat down at the rickety old upright piano began playing along.

And it was effortless.

We knew each other’s timing and temperament so well that by the end we were singing in perfect harmony. And when we both hit the Robert Plant wailing high notes at the rousing end, the house erupted with applause.

We were a hit. We were Unplugged years before MTV came along.

As tight as we became that summer, though, I always felt a distance between us. He was secretive, and he didn’t let too anyone get too close. That was OK, because, guess what: I was the same. We shared the same secret.

In retrospect, I intuitively knew he was gay. But we never dared talked about it. Hell, I couldn’t even admit it to myself back then. Those were scary times in the late 70s in red Baptist eastern North Carolina. They still are.

A couple years after that summer, I went off to college, and Henry and I fell out of touch. I’d see him at parties when I came home. We’d chat, but something was different. He was burdened and melancholy, and I knew what was bothering him.

I never delved any deeper, though, and I’d go back to school, throw myself into my studies and the girlfriend I had at the time, all the time skating the thin ice of denial.

The ice in Henry’s case wasn’t able to withstand the burden. I heard that Henry began to fall apart. He dropped out of college, played keys in a local band at night, and spent most of his day in a drug-induced haze.

In February, 1985, my mother called me to tell me that Henry had committed suicide.

He tied a cinder block to his ankle and jumped off a bridge into the Tar River not too far from where we used to hang out at the end of a dirt road, get high, and crank Zeppelin on the 8-track.

He had been arrested for taking indecent liberties with a minor just the week prior.

His death threw me under a bus that had been careening in my direction for a long time. I knew why he did it. His arrest was only the denouement.

Of course, all the what-ifs plagued me for months. I felt guilty as I replayed our friendship and ran it through all the alternative, happier endings.

But I in the end, I knew I couldn’t have saved him. The only person I could save was myself.

From that moment on, the crack in my closet door began to widen ever more furiously.

Now, 35 years later, that damn door is history. Still, some days, like today, I think about Henry and silently thank him for his gentle unconditional friendship. He was the first true, gay friend I ever had.

I wish he was here so I could tell him that. I wish we had been able to tell each other our secrets. I wish he had held on long enough to see what a progressive world this has become. With all its hatred and bigotry, we’re still light years ahead of the darkness of high school in Greenville in the Seventies.

But I understand why he had to go. Because for a short while there, it was me who was standing on the edge of that same bridge on a late winter night, looking down at the black water, wanting so badly to be loved.

The difference is that, ultimately, I never lost hope that I would.