In the late 1980s, I began work on a genealogy of my father’s family. At that time, all I had to guide me was curiosity, a few newspaper clippings in a family scrapbook, and my father’s dim recollections of his family tree.

This was long before the advent of the internet, and most of the work involved diving deep into musty old papers, wills, land deeds and marriage records in the libraries and county offices of North Carolina.

Fine with me. I love research and discovery. I was living in Greensboro, halfway between my father’s ancestral home in the Appalachian foothills and the state archives in Raleigh, so all was in easy reach.

I did not know then that I was about to embark on what would ultimately become a 20-year search (that continues today) for my entire family’s history. What I found was a tale that is as American as America itself.

I found immigrants who fled the religious conflicts in Germany in 1763 and braved the North Atlantic Ocean for the promise of a better life.

I uncovered the forgotten challenges faced by pioneers who carved their lives out of the North Carolina wilderness.

I met patriots who rose up against the oppression of King George III. I met every day laborers and farmers trying eke a living out of an untamed land.

And I found deep connections to the Civil War and slavery.

Like most Southerners, I’ve always had a fascination with the subject. Part of that stems from my childhood in eastern North Carolina where I was surrounded by children of the Confederacy. As young child who didn’t know any better, I tended to mimic some of the racist behavior I saw and heard on the playgrounds.

In seventh grade, I rode the school bus each day, and there was a Black kid on the route who mercilessly bullied me. One afternoon, after I arrived home, my brother and I were sitting at the kitchen table having a snack. My Illinois-born, progressive hippy mother was across the room cooking dinner. I was telling my brother about that day’s encounter with this bully, and I used that word.

Nigger.

Out of the blue, my mother’s arm grew 20 feet, came at me from across the room, and connected with the side of my head in a full-fisted right hook that knocked me out of my chair.

When the stars cleared, she was hovering over me.

“The next time I hear you say that word,” she said, “I’ll do worse.”

I learned several valuable lessons that day. First, she wasn’t having that bullshit in her house. Second, I had no doubt she would honor her promise of murder. Third, that word was ugly and hurtful.

Fast-forward 15 years to the day I met my Civil War ancestor, Andrew J. Hause, in the North Carolina State Archives. His life was well documented, and he became the focal point of my research.

He was a bricklayer born only a mile from where his great-grandfather had settled after emigrating from Germany. Two days after Fort Sumter fell, he and 12 of his brothers and cousins joined the rebellion. He was placed under Robert E. Lee’s command in the Virginia Theater and in 1862, in a battle outside Richmond 80 miles up the road from where I live today, he was shot in his left eye.

He survived the wound, spent nine months in a Richmond hospital, and was released. He returned to his home in Spartanburg, South Carolina, blinded in one eye, the bullet still in his head. He died in 1906 at 83 years old, the last Confederate veteran in his county.

His tombstone is inscribed with this:

“No monument of fame rear o’er the lonely bed

But carve beneath his name on a stone above his head

A man who wore the gray here slumbers with the dead.”

As I dug deeper into the records, I realized that he and his people were not landed gentry. They were millers and small farmers and house painters. None owned slaves.

At the time, I used the well-worn justification that they couldn’t have possibly rebelled against the Union because they supported slavery. I assumed that, like their grandparents who had rebelled against an unjust King, their motivation was rooted in protection of their homeland against foreign invaders.

In subsequent years, as I strode into the wider world, I began to more fully comprehend the terrible impact of slavery on our collective psyche. I began to cultivate friends who were working to heal the racial divide, and I engaged in conversations with Black scholars and friends who explained the depth and breadth of the injuries that remained.

It was our original sin as one author labeled it–a moniker that resonates with me today. Slowly, I began to question the pride I felt in my Confederate heritage.

And then came the Internet.

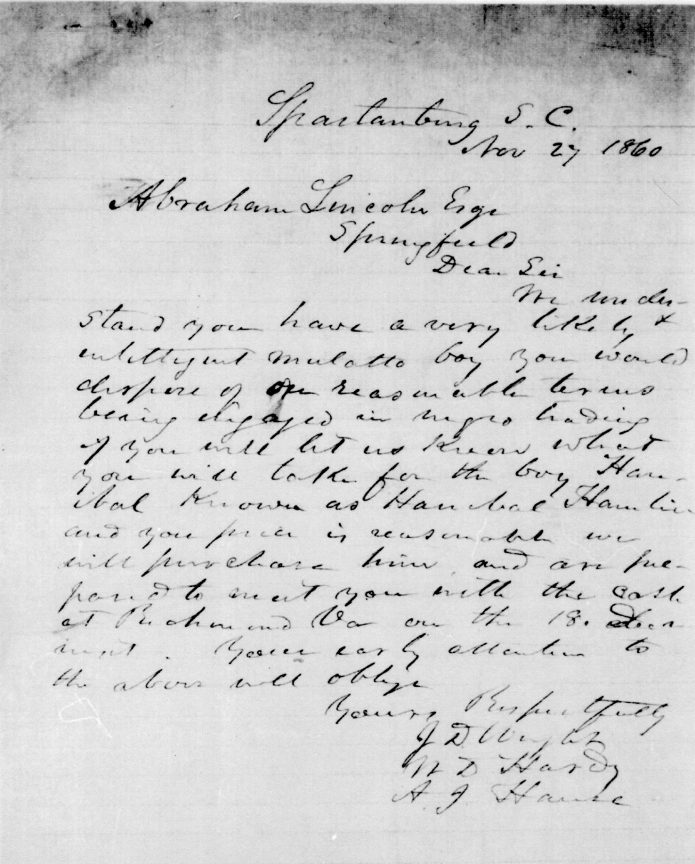

One evening about 20 years ago, I sat down at my computer and Googled “Andrew J. Hause.” Several results returned, and one caught my eye: “AJ Hause, LD Wright, and WD Hardy to Abraham Lincoln: South Carolinians Offer to buy Hamlin.”

It was a letter archived in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Papers in the Library of Congress. I pulled up the letter’s image, and in a handwritten scrawl that may have been my ancestor’s, I read the words.

At first, they made no sense:

“Spartanburg, S. C.

Nov 27 1860

Dear Sir

We understand you have a very likely & intelligent mulatto boy you would dispose of on reasonable terms being engaged in negro trading if you will let us know what you will take for the boy Hannibal known as Hannibal Hamlin and your price is reasonable we will purchase him and are prepared to meet you with the cash at Richmond Va on the 18 Decr inst. Your early attention to the above will oblige

Yours Respectfully

J D Wright

W D Hardy

A.J. Hause”

I had so many questions. Who was Hannibal Hamlin? Why were Andrew and his friends offering to buy him?

After further Googling, I discovered that Hannibal Hamlin was a Senator from Maine and Lincoln’s running mate in the 1860 election. Southerners were terrified that Lincoln and Hamlin would win the White House and abolish slavery.

To exacerbate that fear, Southern newspapers perpetuated a rumor that Hamlin, who had dark hair, a wide nose, and vaguely dark features was of mixed race and thus an agent in Lincoln’s abolition agenda. Most Southerners took it as gospel, and apparently my ancestor did as well.

Along with that discovery came some disturbing, long-forgotten memories of my father’s family. They floated up from my childhood like lava from a long slumbering crater.

I remembered my grandmother’s housekeeper Rosa. She was 300 pounds of pure African love, had a huge grin and raucous laugh that I loved, and spoiled me rotten on my summer visits to my Mema’s house in Shelby, NC

I loved her to death.

We sat in her tiny back room, watched soap operas, and poured peanuts into our Coca Colas while she ironed every napkin, every sheet, and every stich of cloth in that huge house.

My grandmother, while never overtly ugly towards her, was stern and treated her with only minimal respect. Rosa was not welcomed in the main house unless she had been tasked with flipping mattresses or invited to fix a plate to take back to her room.

I then remembered an incident that happened once while my grandmother was visiting us in Greenville. Our next-door neighbors, the Norcotts, were a Black family with a son about my age, Joe. We were carefree kids, and my brothers and I played together with him most days after school.

My Mema was visiting when he came over one afternoon to watch TV. After he left, my grandmother sat me and my brothers down and admonished us. “Boys, it’s fine to play with them,” she said, “but it’s not right to invite then into your house.”

I then recalled another incident involving William, my best friend in junior high school. He lived across the river with his adoptive aunt. He would often come home with me after school, and we’d hang out, listen to records, and gossip about the day’s events.

He and I talked on the phone every night after dinner, and we’d turn each other on to the music of the mid-70s by playing each other the latest 45s we had bought. We walked the halls of the school dishing on everyone and laughing our asses off at those who didn’t get it. We were writers and to each other’s delight, swapped putrid little stories we had banged out on our manual typewriters.

As an aside, twenty years later, I caught up with him briefly, and we told each other what we already knew: that we were both gay. Then we drifted apart again.

I miss him now because I realize now that he was my first real “sister.” I loved him, and I hope he’s reading this because he was at the center of a shift in my understanding of racism, my family, and my history.

The pivot point was one stellar Saturday afternoon in the summer of 1976. William and I hadn’t seen each other since school recessed, so at my invitation, he rode the City bus to my house.

We went up to Pitt Plaza where we bought a hot dog and fries at Eckerd Drugs’ lunch counter, then went next door to the Record Bar where the clerk put on some of the latest albums we wanted to sample.

When we got back to my house, we were hot and sweaty.

He asked, “Can I take a shower before I go home?”

I directed him to my dad’s bathroom so he could have some privacy. Afterwards, while my mother drove him home, my father approached me.

“Did you take a shower in my bathroom?” he asked. He was very proprietary about his space.

“No,” I answered, “My friend William was over here, and he did.”

“William?” he asked. “That Black kid?”

I nodded yes.

He was very quiet for a minute. Then, without another word, he went into his bathroom and scrubbed the shower from top to bottom.

As I sat in from of my computer 20 years ago with Andrew’s letter in front of me, these memories jostling for space, the epiphany that racism had woven its insidious tendrils through the succeeding generations of my family, right up to my father, and cast a cold shadow of bloody original sin right at my feet.

My ancestor’s role in history was then clear to me. He was a racist, pure and simple.

There was no way around that now, and all the romanticism and justification in the world could not excuse it.