By Eric Hause | Copyright by the author

It was Alexander Hamilton who coined the nickname that has stayed with the seas off North Carolina for 200 years: Graveyard of the Atlantic. In 1773, a 15 year-old Hamilton was caught off Cape Hatteras in a furious storm which nearly sent his ship to the bottom of the Atlantic.

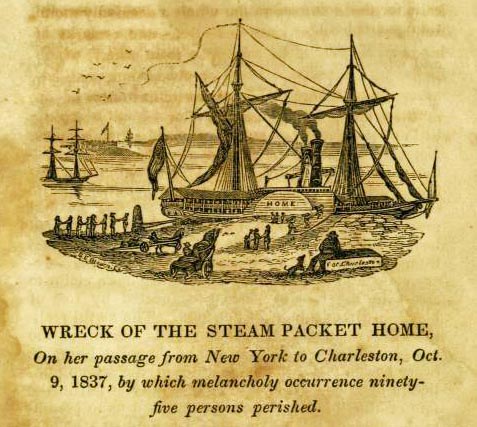

When the steamship Home left New York Harbor for Charleston 65 years later, none of the 135 passengers and crew had any inkling of Hamilton’s experience–or that they were headed directly into the teeth of a similar storm that would have a much more tragic result. The illustrious passenger list read like a Who’s Who of the day, and the only thing on most of their minds was that they would hopefully be a part of a record-breaking ocean passage between the two cities.

The Home had done it twice before. The sleek steamship was the pride of a growing fleet of steam packets that plied the waters off the East Coast in the days prior to the Civil War. Steam-powered side wheelers were rapidly becoming the most popular form of transportation in the country, and the Home was the creme de la creme of these newfangled vessels.

Originally constructed for river trade, the 220-foot ship was converted to a passenger liner by James Allaire, a wealthy New York businessman. The ship’s interior was paneled in deep mahogany and cherry wood with breathtaking skylights, saloons and luxurious passenger quarters. Allaire spared no expense in making the Home the most plush vessel of its type. But in an oversight that would prove fatal, he equipped the ship with only three lifeboats and two life preservers.

At peak performance, the Home could easily make 16 knots, unheard of in the days of sail. She embarked on her maiden voyage in the spring of 1837. On her second trip that year, she made it from New York to Charleston in a record-breaking 64 hours. The steam packet immediately became the hot ticket for the wealthy and prominent citizens of the day. When a third voyage was announced in October, 1837, the Home’s ticket office was swamped with reservations.

The Home pulled away from the New York docks on October 7 at full capacity, with 90 passengers and 45 crew. Some of the most prominent names of the day were on board: Senator Olive Prince of Georgia; James B. Allaire, nephew of the owner of the Home; and William Tileston, a wealthy Charleston entrepreneur who carried more than $100,000 in notes with him. A majority of the passengers were women and children.

Meanwhile, off the coast of Jamaica, a hurricane was gaining in intensity. Dubbed ”Racer’s Storm,” the cyclone would cross the Yucatan Peninsula, slam into Texas, then curve east over Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia before emerging in the Atlantic off the Carolina coast.

In the annals of hurricane history, Racer’s Storm wasn’t a particularly violent storm. But steamships like the home were not built for ocean travel. The long, sleek packets were originally designed for calm river trade routes and were dependent solely on steam for power. They rode low in the water, and the slightest ocean chop sent water sloshing into the boiler room.

So when the Home encountered the fringes of Racer’s Storm off the Virginia Capes, Captain Carleton White became concerned. A boiler pipe had burst earlier in the day, and the ship was difficult to control under reduced power. As the storm grew in intensity, the steamship drifted ever closer to the northern Outer Banks shoreline, and Captain White had just decided to beach the vessel when word came from below that the pipe was repaired. Captain White ordered full-steam ahead, not knowing that he was taking his ship and passengers directly into the teeth of the storm.

Several hours later, a huge wave broadsided the Home, sweeping everything above deck and sheering off part of the bulkhead, leaving all the cabins on the port side exposed. Water cascaded into the boiler room. Captain White ordered the passengers and crew to form a bucket brigade to prevent the rising waters from extinguishing the boiler fires. Barely under power, the ship limped around Cape Hatteras on the early evening of October 9.

Finally, at 8 PM, the boiler fires went out and the ship was drifting helplessly. Captain White had no alternative but to beach the ship. He raised the small auxiliary sails, tacked to the west, and headed straight for the beach on Ocracoke Island. He had the three lifeboats readied and assembled the 135 passengers and crew.

The situation was desperate. Confusion reigned on the once-proud liner as men, women and children scrambled to carry what they could to the decks. Finally, the breakers along the shore were spotted in the distance.

In his published account of the disaster, Captain White described the grounding: ”I ordered Trost, the man at the wheel, to port his helm; I then said to Trost, ‘Mind yourself, stand clear of that wheel when she strikes, or she will be breaking your bones.’ He answered, ‘Yes sir, I will keep clear.’ The boat immediately struck on the outer bar, slewed her head northward, the square sails caught aback, she heeled offshore, exposing the deck and upper houses to the full force of the sea.”

It was about 10 PM when the Home grounded about seven miles east of Ocracoke Village. The towering breakers raked the ship in terrifying succession, and within minutes, most of the people gathered on deck had been swept into the raging surf. One of the three lifeboats was smashed when the ship struck, and panic ensued as the passengers made for the remaining two boats. Two able-bodied men commandeered the two life preservers and jumped into the sea. They made it to shore alive.

It was about 10 PM when the Home grounded about seven miles east of Ocracoke Village. The towering breakers raked the ship in terrifying succession, and within minutes, most of the people gathered on deck had been swept into the raging surf. One of the three lifeboats was smashed when the ship struck, and panic ensued as the passengers made for the remaining two boats. Two able-bodied men commandeered the two life preservers and jumped into the sea. They made it to shore alive.

One lifeboat filled with women and children as launched but capsized as it hit the boiling surf. The last boat landed upright but also sank with a few seconds. The sea was filled with screaming women and children. One witness later said he doubted that anyone in those two boats survived.

As midnight approached, the Home began breaking up. Each wave carried away more passengers. Others took their chances. One female passenger lashed herself to a settee and floated to shore, waterlogged but alive. Another woman tied herself to a wooden spar and jumped into the surf. She too made it to shore.

In one ironic instance, two brothers, Philip and Isaac Cohen jumped into the surf. The brothers had been wrecked off the Carolina coast on another ship only a year before. Now they were faced with a much more critical situation. Isaac made it to shore safely, but his brother drowned.

Captain White and seven others had taken refuge of the forecastle deck, and as the ship disintegrated, the forecastle broke free and carried them safely to shore. By 11 PM, all that was left of the Home was its boiler, which rose above the waves like a monument to the 90 people who lost their lives that night.

Dawn broke over a hellish scene. The Ocracoke beaches were littered with debris and bodies. The villagers, accustomed to wrecks on their shores, took in the survivors and buried the dead anywhere they could. The survivors–mostly men–were ferried across the inlet to Portsmouth where they gained berth on outgoing ships. White remained on the island for three days to supervise burials of the victims. He then returned to New York only to face charges of negligence and drunkenness.

For years after the disaster, the Captain answered these charges. He wrote his account of the disaster, but the wreck of the Home was the most deadly sea disaster on American shores at the time, and his reputation was ruined. The long-lasting effects of the disaster were more positive. As soon as the news became widespread, ship owners voluntarily equipped their vessels with adequate numbers of life preservers. The next year, Congress passed The Steamboat Act, which required all passenger ships to carry one life preserver for each person on board.