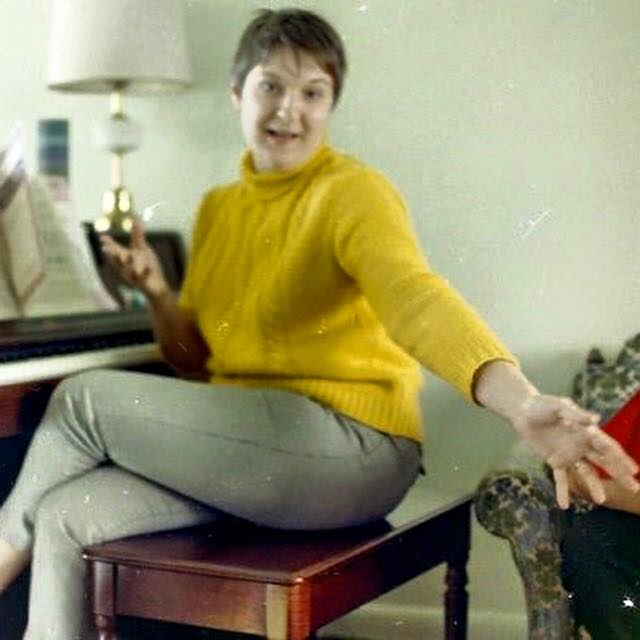

Richmond native Emily Skinner is the epitome of Broadway’s leading lady.

Over her 26 years in the biz, she has played leading roles in such Broadway productions as Prince of Broadway, Jekyll & Hyde, James Joyce’s The Dead, The Full Monty, Dinner at Eight, and Billy Elliot.

Skinner’s role as one half of a pair of Siamese twins in Side Show earned her critical acclaim and a Tony Award nomination shared with co-star Alice Ripley

She recorded an excellent self-titled solo album, which was released in 2001, and she has sung with orchestras around the world.

This winter, she will appear in The Cher Show as Georgia Holt, Cher’s mother, in the Broadway run at the Neil Simon Theatre which begins previews November 1.

This Saturday night, she comes to Hampton Roads as the headliner at the Hampton Arts 31st Anniversary Gala, an invitation extended by Richard Parison, artistic director and a friend since their days in Richmond together.

It’s amazing to look back over your career how much you’ve been involved in. Just the last two years alone is impressive. When do you sleep?

It’s good to be busy and have diverse projects. I really love my career, and I’ve worked hard to get here.

What can we expect from your concert this week at the Hampton Arts Gala?

I think pretty much everything. Everything I’m going to sing is from Broadway. I like variety, so I try to mix up the program with a wide range of classic stuff and contemporary stuff. I’ve got everything in there: Sondheim, Rodgers and Hammerstein. I even have some Mae West.

You have bounced back and forth from Broadway musical to Cabaret to stage actress and recording artist. What jazzes you the most?

That’s so hard! I really like it all. When I sing a lot, there’s a part of me that says, “Gosh, I wish I was doing a play.” And when I’m doing a play, I want to do a musical. It’s good to go back and forth and hit everything. I sort of feel like when I’m performing a musical or cabaret, it tends to be a little more a giving to the audience. Versus when I’m doing legit acting, it feels a little more internal.

Do you have any new recordings in the works?

The Cher Show cast album will be out at the beginning of the year, that’s the big one.

Speaking of the Cher Show, wow, Georgia Holt. What an iconic role to play.

She’s an interesting mother.

How did you prepare to play her?

I was asked to audition for the show, and I didn’t really know anything about Cher’s mom. So I Googled her and watched lots of footage of Cher and her mom online, including the documentary that Cher did about her. I have this weird thing when I’m asked to go on auditions. I have to be able to visualize myself playing the role, or I don’t bother. And as soon as I started to watch Georgia, I thought, yeah, I know who she is. I can do this.

They put my audition on tape for Cher so she could have final approval on casting. She caretakes her mother in such a beautiful way, so I was incredibly honored when I got the part. I knew Cher sat there in her Malibu home, watched the tape and picked me.

I read that after the pre-Broadway run in Chicago, Cher said she loved it, but in typical Cher fashion, said it needed a little work.

And she’s right. And that’s why we love her. She’s such a straight shooter, uncensored. No pretense, no bullshit.

And now you’re taking that role to Broadway this autumn.

Yes, we start rehearsals right after the Gala on October 1, and then it’s out there.

I was intrigued in your participation in the AIDS themed Elegies for Angels, Punks, and Raging Queensback in the day. How did you get involved in that?

Oh my gosh, this is such a weird story. I had first heard the song My Brother Lived in San Franciscoyears ago when I was in college. And I thought it was a beautiful song. When I auditioned for Sideshow, I actually used that song. At the end of my audition, there were a bunch of people in the room, and a guy stood up from the table and said, “I wrote that song.” And it was Bill Russell, who wrote the music for Elegies and for Side Show.

I was so lucky to be in that production, and I’ve been in different versions of it over the last 15 years. It’s such a moving and beautiful show. The monologues that make it up are knockout, and the songs are gorgeous. I’m so happy it keeps getting done.

You were in the original cast of Prince of Broadway, which debuted in Tokyo. Is there any difference between American theater audiences and Japanese audiences?

Well, you know, I will say in Asia they love American musical theater. They’re wild for it. So our audiences were crazy for that show. There’s really very little book in that show. It’s literally back-to-back 11 o’clock numbers from Harold Princes’ shows. And most of the shows, Phantom and West Side Story, they’re in our musical consciousness internationally. Everyone knows them. I think in the future they’re going to continue to play that show internationally because it did do well in Asia.

I was looking at the impressive roster of your leading male co-stars over the years. Who are some your favorites?

Oh, that is so hard! I did a show with Chris Walken years ago, and he is a riot. He’s so on his own special planet. He was wildly kind and entertaining to work with. He was always trying to keep things fresh, and he always had things in his pockets. Sometimes he would pull out peanuts, shell them, then throw them at me. Or he’d take out a pickle and start eating it. So he was a lot of fun.

So you and Alice (Ripley): you two are so fantastic in everything you do. How in your mind has that relationship evolved over the years?

We sort of yin and yang each other. We’re wacky. It’s funny, they say we become more of who we are innately as we age, and that’s definitely true of Alice and myself. We’re both super busy with our own projects, but we do get together on some concert stuff occasionally. We have a new show coming up in January.

You also have your own show, and I get this affinity from you for the classic Broadway musicals of the last century.

I grew up with a mother who loved classic Broadway, and she had a cast album collection. So I grew up listening to that. That’s always where my first love is. That’s when people really knew how to craft, you know? They knew how to sit down and write a three-page song that would knock you in the guts. And when you have great material, you really don’t need to bell and whistle things up.

I read something about one of your early teachers in Richmond giving you a hot minute in class to perform.

Yup, that’s true. So many times kids these days get diagnosed with ADD, and many times all they need is an outlet. I am a case study of that kid. I was so manic. I was so hyper. They weren’t going to pass me on to first grade.

At some point towards the end of my kindergarten year, my teacher said, “OK Emily, you’re going to get 15 minutes every day to entertain the class.” And that was the opening of Pandora’s box. After about three weeks of this, my teacher called my mother and said, “I just thought you should know that you have an entertainer on your hands.”

That was an early and correct diagnosis!

Yes, she was right. So always think that if I ever won anything in my whole life with regards to the theater, I would stand up and thank that kindergarten teacher.